Ok, here is the short version of the argument on why the "power law outcomes" is probably not the *only* way to invest in early stage tech companies these days twitter.com/tylertringas/status/1513333150457421828?s=20&t=fFf09zxBACFbZPsTjuU-gQ

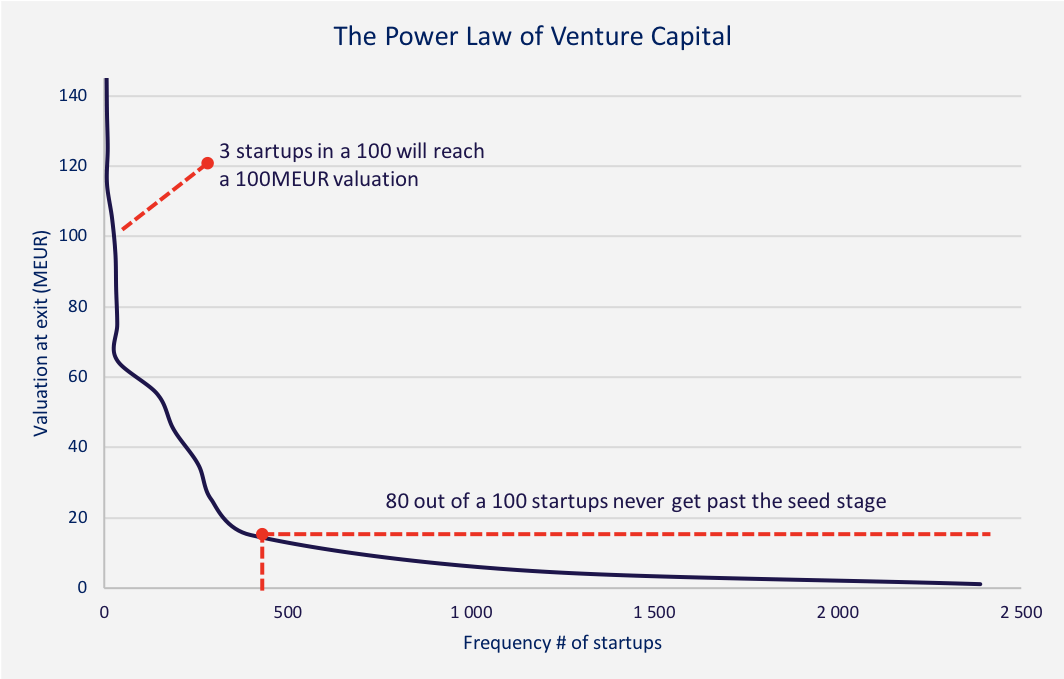

First what do we mean by power law? Over time most successful VC portfolios end up looking like this, lots of failures + almost all the returns coming from a very few tiny % of the investments. So these days, VCs optimize for these extreme outlier power law outcomes

In many ways this is awesome. Venture Capital, when done well, making big bets on breakthrough technology, can afford to back a lot of things that fail if they get 1-2 grand slam outliers. This distribution is how VC can invest in all kinds of crazy tech, some of which works!

Although the data is still somewhat messy, I don't think it's in dispute that "successful venture funds have almost always had this kind of distribution"

The question is whether this is the only way that works, or the only way that the small number of people who do VC have tried

If you zoom back out to the level of "investing in entrepreneurs at the early stage" you can see pretty quickly it's not always going to be power law. Back 100 entrepreneurs starting McDonalds franchises, you're not gonna see any grand slams. Returns will be drive by % successful

So "grand slam hunting" can't be the only viable way to invest in entrepreneurs. Now we need some tools to analyze a market or set of opportunities to determine if we should be optimizing for outliers or optimizing for hit rate.

I'd argue you need 3 factors for a market to warrant the traditional VC model:

1/ High startups costs

2/ High technical risk

3/ Winner-take-all market dynamics (network effects, green field first-mover advantage, economies of scale, etc)

So the crux is, does the market for software businesses have these three factors. I'd argue that 10-20 years ago it absolutely did:

1/ It cost like $2m to ship a basic iOS app

2/ Many underlying software technologies were still nascent

3/ Many opportunities had zero incumbents

But in each of these factors I believe the software market has changed radically in the last 10 years such that none of these factors are currently true:

1/ are startup costs high? No! They're down by at least 10x. A single indie hacker can ship a feature-complete competitive SaaS product in their spare time. The driving force is the Peace Dividend of the SaaS Wars twitter.com/tylertringas/status/1213183939382087680?s=20&t=7md8rmLcZEEGkm74tnJYsQ

2/ Is there high technical risk? Largely no. Most software businesses leverage a patchwork of existing frameworks, tools, open source modules, and blank-as-a-service products to reduce the risk of "can they actually build this?" to near zero.

3/ is the market winner-take-all? It used to be but it ain't any more. There are now many massive publicly traded incumbents in almost all major verticals (CRM, e-commerce, CMS). Companies can still be successful, but are far less likely to run away with the whole market

So I would argue that, while it has been true in the past that the market opportunity in software mapped well to the power law distribution approach to investing, it's simply no longer true as the market for software is entering an entirely new phase

The good news is that this unlocks a huge new opportunity: to invest in software companies without having to be a "grand slam hunter." But it requires a fundamentally different fund strategy, re-built from the group up to back, what we call "calm companies"

So what makes a calm company successful? Well it's complicated and it's a skill we're developing and honing ourselves, but here are the key questions I ask myself before any investment as a starting point calmfund.com/writing/investment-questions