Stories of Freedom - The Insurgent Mayor of Czernowitz / Cernauti / Chernivtsi in todays Ukraine.

When Germany signed its non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in it took Besserabia and Northern Bukovina from Romania and gave it to the Soviet Union.

twitter.com/FAB87F/status/1738604550469083254?s=20

In July 1941, when Germany attacked the Soviet Union with Romania at its side, the two territories were returned to Romania.

For three days the returning Romanian soldiers carried out a massacre among the local Jewish population.

Born in 1892, Dr. Traian Popvici was the son of a Romanian Orthodox priest. He studied law in Czernowitz (Cernauti – the former capital of Bukovina – and today Chernovtsy in Ukraine) and earned a doctorate.

When Soviet Russian annexed his town he moved to Bucharest.

At first he supported Ion Antonescu's regime, but soon became disenchanted with its policy of segregation.

When Czernowitz was returned to Romania in July 1941, Popovici was appointed mayor.

By the time he moved into the mayor's office, some anti-Jewish decrees had already been enacted, and he tried to alleviate the Jews’ situation as much as he could.

According to testimonies all persecuted Jews turned to him for help.

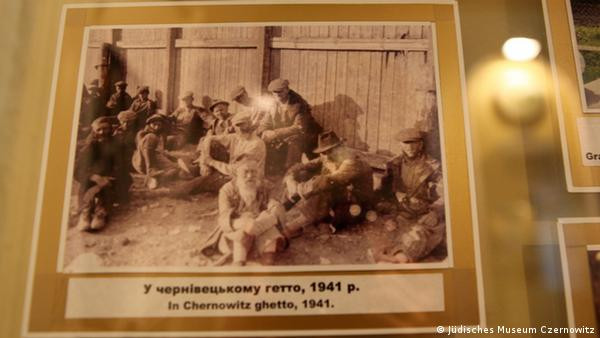

On 10 October 1941, the Romanian governor, acting on Antonescu's orders decreed the creation of a ghetto and the deportation of the city's Jews. Popovici expressed his objection, but to no avail.

On October 11, 1941, the order was given for all Jews to gather in the poorest neighbourhood of the city within 24 hours. The ghetto became the staging area for deportations, which began two days later.

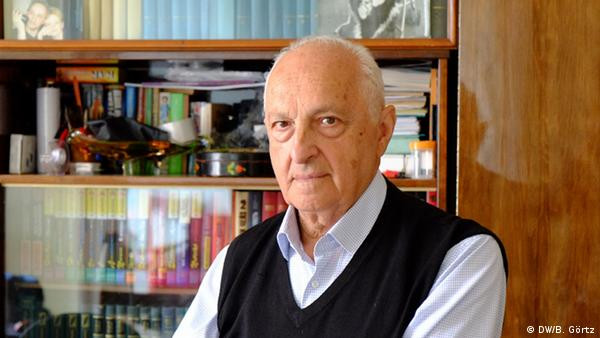

Josef Bursug survived the Transnistria Holocaust. "My family was lucky not to be killed in the early days of the genocide. We weren't caught in the ghetto or arrested during police raids," he said. Bursug was 10 years old when German and Romanian troops occupied his homeland.

"People from the ghetto were taken to the train station every day, crammed into wagons and sent off to Transnistria," Bursug recalls.

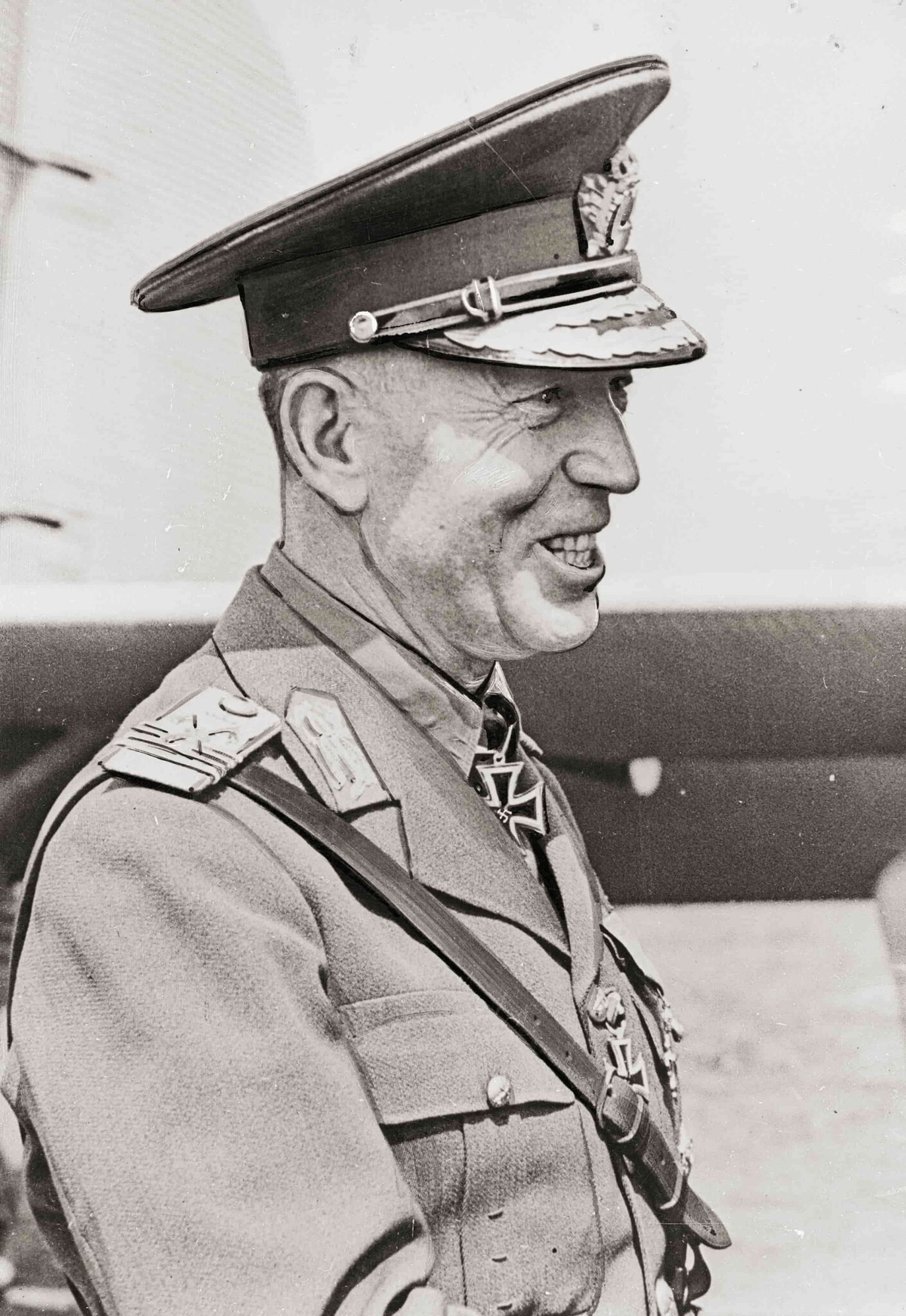

The man in charge at the time was the governor of the Chernivtsi region, General Calotescu.

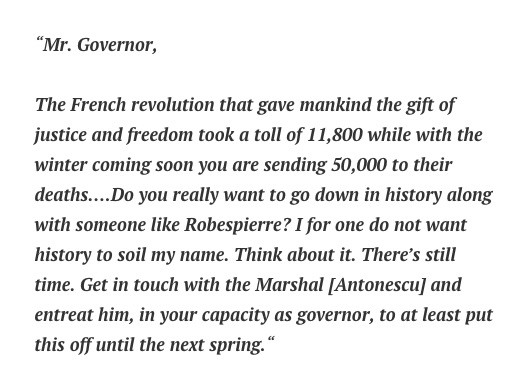

The mayor, Traian Popovic, urged him to halt the deportations, arguing that if all the Jews were sent away, there would be no shoemakers, tailors or plumbers.

The governor acquiesced to exempt 200 Jews only from deportation but Popovici did not give up and managed to reach Antonescu himself, arguing that the expulsion of the Jews would be a mortal blow to the economy of the region.

He succeeded in securing a postponement which resulted in the saving of some 20,000 Jews.

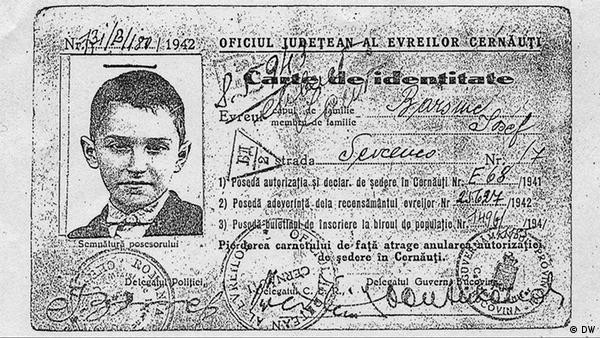

A commission was set up to identify the needed occupations, and those people and their families were allowed to stay. The people on this list were given what were called authorization papers.

Josef Bursug and his family were among them. He still has the identity card which allowed him to avoid deportation and almost certain death.

Within a few days the deportations began, and Jews from Czernowitz were transported across the river to Transnistria. By mid-November 28,000 of the town's Jews had been deported.

The terrible conditions in Transnistria and the inhuman forced labor led to the death of approximately half of the deportees.

Popovici later described the deportation: "Out there a great column of people was going into exile: old men leaning on children, women with babies in their arms, cripples dragging their mangled bodies, all bags in hand;

the healthy ones pushing barrows or carts or carrying on their backs coffers hastily packed and tied, blankets, bed sheets, clothes, odds and ends; all of them taken from their homes and moved into the ghetto.

In his memoirs Popovici said that he contemplated stepping down, but was determined not to abandon the Jews in their time of need.

Disregarding the risk to his person, he continued to protest to the governor and to Antonescu, arguing that the Jews were vital to the economic stability of the town. His ruse succeeded, and he was ordered to draw lists 20,000 Jews within four days.

The Jews who received the exemption from deportation were allowed to return to their home. Popovici distributed authorizations to Jews - well above the quota he was given, and to people who had no professional skills whatsoever.

The abuse of his mandate cost him his job.

In spring 1942 he was charged with granting permits to "unnecessary" Jews, and was removed from his position and returned to Bucharest. In June 1942 another 5,000 Jews of Czernowitz were deported to Transnistria – most of them perished.

The Jews remaining in Czernowitz survived.

Immediately after the war, Popovici wrote a book entitled Confession of Conscience. He described the events as a Romanian tragedy with deep implications for the moral consciousness of the Romanian nation.

Traian Popovici confessed that he was not an adversary of Antonescu. “Like many others in this country I believed in the myth of the strong man, of the honest, energetic, and well-meaning leader who could save a damaged country."

He went on to describe his motivations in helping the Jews: “As far as I am concerned, what gave me strength to oppose the current, be master of my own will and oppose the powers that be, finally to be a true human being, was the message of the families of priests that

constitute my ancestry, a message about what it means to love mankind.

What gave me strength was the education I had received in high school in Suceava, where I received the light of classical literature, where my teachers fashioned my spirit with the values of humanity, which tirelessly enlightens man and differentiates him from the brutes”.

It should be noted, of course, that many who had received the same education were among the perpetrators and bystanders, and that on the other hand, many rescuers did not enjoy and enlightened education at all.

The answer to the question what prompted certain people to preserve human values is more complex.

Popovici died in 1946.

Twenty-three years later, in 1969, he was recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations -- the first Romanian to receive this honor.

Paying tribute to Popovici in his own country took longer.

In June 2000, by resolution of the Bucharest town hall, a street in the Romanian capital was named “Dr. Traian Popovici,” after the former mayor of Cernăuţi during the Second World War, who saved thousands of Jews from deportation to Transnistria.

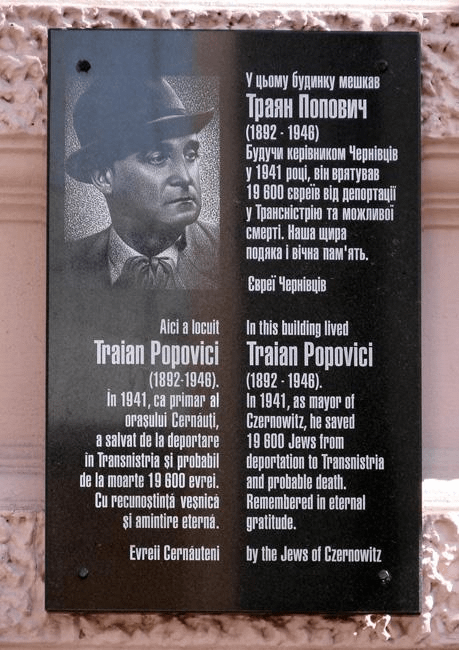

On April 20, 2009, a plaque was unveiled on the building that had been Popovici’s house in Czernowitz, located at 6 Zankovetska.

In a ceremony attended by representatives of the Jewish community, Popovici Society (from Romania), the Ministry of Culture of Romania from the Consulate of Romania in Czernowitz, and visitors from Israel and the United States.

The plaque contains text in Ukrainian, English, and French that reads: “Here lived Traian Popovici (1892 – 1946). In 1941, as Mayor of Czernowitz, he saved 19,600 Jews from deportation to Transnistria and probable death. Remembered in eternal gratitude by the Jews of Czernowitz.”

A memorial to the Jews of Chernivtsi murdered in Transnistria during the Second World War.